There are two souvlaki houses in Symi harbour, but both turned

out to be closed until the New Year. A lot of islanders went away for the

holidays, and you can’t blame them after two Covid years and then a financial

recovery year which was exceptionally busy. A bar had burgers and club

sandwiches, but they said one restaurant was open around the harbour. I wanted a

big dinner as fuel for walking the next day.

The restaurant was open, empty (it was early), didn’t

have any of the oven-baked food I’d hoped for, and was quite expensive. The salad was mostly rock-hard tomatoes. But

it had a nice view over the water, friendly people; gradually other customers

arrived, a group of English people who had a house here, and two frozen-looking

Germans who’d arrived on a boat and ordered tea and fava.

The owner came to talk to me when he wasn’t busy, and I was

pleased to chat in Greek – I don’t get enough practice at home. Asked if I was

staying for New Year’s Eve, I explained I’d like to but would have to find a

cheaper place to stay. By the end of the evening, I was being offered a room, an extra slice of cheesecake and dinner on the house… and a waitressing job.

So I did wake next

morning with a certain anxiety. How do these things happen? No matter, it could all be resolved later.

It was 28 December, and outside my windows that looked

straight out onto the water, cars and scooters were zipping about. The sun

briefly hit the other side of the harbour around 9 a.m., then went behind a

small cloud, and everything was still damp and cool, though forecast to get

warm. I made myself a Greek coffee and sat on the lovely balcony, listening to

cockerels crowing somewhere back around the Kali Strata, the steps that lead up

to the Horio flanked by mansions from the late 1800s.

Despite visiting Symi several times – often for its great hardware shops, I must admit, though with good walks also – I’d never been up high in the centre of the island on foot to see the old wine presses. These sunny, bright winter days were perfect for it, though I’d have to set out by mid-morning given it was getting dark soon after five.

We set out inland from the back of the harbour to reach the cemetery at Elikoni, didn’t see any markings for the path from there that was on the

map, but found a way up the dry riverbed a bit and through gates, passing sheep

that approached rather than ran away, until suddenly there was a beautiful old

stone-paved donkey path or kalderimi that twisted back and forth up the hillside,

making the going easy all the way to a church or two and small group of houses.

It was a wonderful start. By then we were already in very warm sunshine – I wished

I’d been able to dip Lisa in the sea before we set off – and lovely countryside.

Turning left, we followed the gradually ascending road past the Xisos turn-off and eventually to meet the main road that crosses over the top of the island and heads down again on the other side to the big monastery of Panormitis. Thankfully at this time of year there was no traffic, just the sound of sheep bells (and a jackhammer far below, of course, this also being perfect weather for construction work).

There was a nice little detour on a kalderimi again, beside a field where someone was burning olive branches, to the chapels of Ayia Katerina and Panayia tis Stylou (tempting to think of the name as a corruption of tis Tylou, ‘of Tilos’, since there was a view of our island!). After a couple of hours of ascending, it felt as though we were in the uplands, the road unexpectedly winding around cultivated valleys scattered with monasteries, and eagles and crows circling around Vigla peak just above (617m, the highest on the island), with what looked like a broken wind turbine.

I had decided to aim for the ‘Pano Krasokelia’, Upper Wine

Presses, following the directions in Kritikos Sarantis’ booklet Discover

Symi on Foot – copyright 2007 but bought here just a couple of years ago so

hopefully it wouldn’t be too out of date – along with an also locally produced

walking map. Blue and red paint dots also marked paths here and there.

Passing the padlocked monastery of Ayios Konstantinos , I continued

to Ayios Nikolas as directed, but there was no sign of the path if I was

reading the instructions right. There was a truck outside and washing hanging

to dry, but nobody to ask. After a few attempts to find the way across rough

ground with gates very tightly wired shut, I had to give up. Perhaps on my own

I’d have tried harder, but it wasn’t worth making Lisa walk through fields of thistles.

Back to the road, instead I took the turn a few minutes later to Kokkimidis, following a narrow, pleasant concrete track that ran below those elusive wine presses into beautiful hilly uplands, with enclosures where again the sheep and goats seemed to approach rather than run, and there was a stone-build pond filled with water. I realised I hadn’t seen anything like the death toll of goats we have on Tilos this winter. Although the fences and gates here might be limiting, the animals were looked after, fed and watered.

The track led to a cluster of historic buildings through gorgeous

countryside, and at some point, someone in authority must have thought: what a perfect

place to throw the old fridges down the mountain! For there, lo and behold, was

that scourge of the Greek islands, the edge of the old dump, spilling down the

hillside towards the forest.

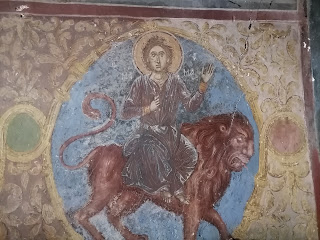

But at Ais Yiannis Tsagrias, the gate wasn’t padlocked, and

the door wasn’t locked, and inside were some of the oldest frescoes on the

island. They were dark, hard to make out, but showed up clearly on my phone

camera and were thrilling to see. Stepping outside again, I felt blessed to

have been able to come to this place and find them, surrounded by spectacular hills

covered in rocks and forests, with a stellar view of our modern-day

contribution, a cascade of rusted appliances.

Just beyond were the remains of an ancient hilltop fort (above: Lisa shocked that you could see the rubbish dump from here too?), perhaps repurposed once as a farm. There was a big stone water cistern, and a little further along a primitive ancient wine press, just a block of stone with a circular carving, in a padlocked enclosure for animals.

Beyond there, past some old stone terraces at the end of the road near large old trees was Kambiotissa, a monastery built like a fortress with tall walls and still seemingly guarded thus with padlocks and fences all around. I tried following the fence around to the back and glimpsed what perhaps was a more recent wine-pressing building, but it was hard to tell.

We were tired, and Lisa was keen to head back, but I decided to take one last detour uphill to the monastery of Kokkimidis, joking aloud to Lisa that this one would make our day, even as I fully expected it to be padlocked and fenced. But hallelujah! A car I’d seen earlier, perhaps the only car in hours, speeding up the road, was parked at the top of the winding track, and the gate open.

I heard voices inside, but seeing nobody, I left Lisa tied to

the fence and tried the door to the church, above which was an old plaque alluding to a restoration in 1697 – and opened it to an astonishing little church, every inch of walls and ceiling painted

with fascinating, beautiful scenes.

The floor was a pebble mosaic, with an interesting bit of graffiti in it: 8.11.1970, Tilos, and some initials, carved into the stone - that must have taken some dedication! Perhaps M.S.S. was the person who made the floor?

It had been a stroke of luck to find the place open; and I'd have missed that if we'd got to the wine presses. And so, we walked back down, in beautiful light, everything still and glowing, the sea glassy, Lisa determined that we should go back exactly the way we came, while I felt we should take the road as dusk was falling. We compromised by trying a bulldozed track which led to a wonderful old kalderimi, which led all the way to the Horio.

From there Lisa guided us down to the Kali Strata, down to the harbour for dinner - and a bottle of wine on special from the old supermarket. 'Kalo Pascha!' the owner with the dry sense of humour wished me, happy Easter, and I looked puzzled. 'I'm getting ahead of myself,' he said, 'can't wait for winter to be over.'